|

|

SAMMY BALOJI E ALICE SEELEY HARRIS‚ÄòWhen Harmony Went to Hell‚Äô, Congo Dialogues: Alice Seeley Harris and Sammy BalojiRIVINGTON PLACE London EC2A 3BA 16 JAN - 07 MAR 2014 Sammy Baloji e Alice Seeley Harris em Di√°logo: Contra os Solil√≥quios de Leopoldo (e de outros)[Scroll down for English version] Rivington Place, a casa londrina do Autograph ABP e do Iniva, tem neste momento patente uma exposi√ß√£o de fotografia not√°vel. Organizada pelo Autograph ABP e comissariada pelo seu director Mark Sealy e pela curadora associada Ren√©e Mussai, esta exposi√ß√£o estabelece um di√°logo, tornado expl√≠cito no t√≠tulo da exposi√ß√£o ‚ÄòWhen Harmony Went to Hell‚Äô, Congo Dialogues: Alice Seeley Harris and Sammy Baloji, entre dois corpos de trabalho fotogr√°fico muito distintos: um projecto em desenvolvimento do fot√≥grafo congol√™s Sammy Baloji (n. Lubumbashi, RDC, 1978), entitulado Congo Urban: Rhythms of Syncopation and Suspension, a sua primeira exposi√ß√£o individual no Reino Unido, que ocupa o espa√ßo expositivo maior de Rivington Place, o Project Space 1, e inclui a colabora√ß√£o de Filip De Boeck e Chrispin Mvano; e no Project Space 2, o arquivo fotogr√°fico, realizado pela mission√°ria brit√¢nica Alice Seeley Harris (1870-1970) em 1904, das atrocidades cometidas pelo Rei Leopoldo II (1835-1909) no territ√≥rio em rela√ß√£o qual as na√ß√µes coloniais europeias e os Estados Unidos decidiram, na Confer√™ncia de Berlim de 1884-85, que deveria ser administrado privadamente por ele ‚Äì o ironicamente chamado Estado Livre do Congo (1884-1908), presentemente, Rep√∫blica Democr√°tica do Congo, o pa√≠s de Baloji. Atrav√©s das s√©ries fotogr√°ficas de grandes dimens√µes e das fotomontagens de tamanho menor que comp√µem Congo Urban: Rhythms of Syncopation and Suspension, Baloji investiga a forma como o passado colonial continua a assombrar o presente nas ru√≠nas arquitect√≥nicas e p√≥s-industriais da modernidade [1]: edif√≠cios modernistas decadentes mas re-apropriados em Kinshasa; sat√©lites enferrujados elevando-se inutilmente na periferia da cidade; as estruturas abandonadas da ind√∫stria mineira (Fig. 1); a segrega√ß√£o urbana racial, implementada em tempos coloniais sob pretexto de salubridade modernizadora, tecida na estrutura de Lubumbashi, a capital de Katanga, prov√≠ncia do sudeste onde Baloji nasceu e uma das √°reas mineiras mais ricas em cobre, cobalto e ur√¢nio da √Åfrica Central (Fig. 2). De facto, um dos componentes mais fortes da exposi√ß√£o de Baloji √© Photographic Essay on Urban Planning from 1910 to the present day in the city of Lubumbashi (2013). Este trabalho √© uma composi√ß√£o de grandes dimens√µes em forma de grelha com vistas a√©reas de Lubumbashi que retratam uma mina e um ‚Äòcord√£o sanit√°rio‚Äô que foi planeado no in√≠cio do s√©culo XX pela administra√ß√£o colonial para proteger a popula√ß√£o branca da mal√°ria; da√≠ a justaposi√ß√£o em grelha das vistas a√©reas, grelhas urbanas de controlo e separa√ß√£o, e de outras composi√ß√µes igualmente em grelha: taxonomias pseudo-cient√≠ficas de mosquitos portadores de mal√°ria, tamb√©m elas t√≠picas das epistemologias coloniais de classifica√ß√£o obsessiva, que Baloji encontrou num museu. Com o intuito de providenciar contextualiza√ß√£o, este trabalho √© acompanhado por uma cita√ß√£o em ingl√™s de The Development of the Congo, um n√∫mero especial que sa√≠u por ocasi√£o da Exposi√ß√£o Internacional de Elisabethville, nome colonial de Lubumbashi, em 1931, no qual R. Wins, um engenheiro provincial de Katanga, escreveu o seguinte: ‚ÄúThe neutral zone avoids close contact between whites and blacks. An almost empty area measuring a minimum of 500 meters separates their two areas of settlement, this distance corresponding to that which a malaria-carrying mosquito will normally cover. The neutral zone thus divides the lives of blacks from those of whites: it keeps the latter safe from the sources of malaria, and from the rowdy activities of blacks, so creating completely independent living conditions for each race ‚Ķ it is a true cordon sanitaire, placed at a right angle from the prevailing winds ‚Ķ our urban planning contents itself with creating developments that satisfy conditions of hygiene, salubrity and security, giving the white and black races the opportunity to live according to the hopes and needs of each, however modest these might be.‚Äù [2] Sem d√∫vida, o apartheid n√£o foi exclusivo da √Åfrica do Sul. Baloji acrescenta mais um componente a este momento da sua exposi√ß√£o: uma fotografia datada de 30 de Outubro de 1929 que retrata dois jovens negros sentados ao lado de uma pilha de insectos, com a seguinte inscri√ß√£o no verso: ‚ÄòLubumbashi MOI, Fly control campaign: each worker must bring 50 flies in order to receive his daily ration, 30 October 1929‚Äô (Figs. 3-4). Agora sabe-se como a colec√ß√£o de mosquitos fotografada por Baloji foi reunida por cientistas coloniais, como a mal√°ria foi prevenida, e quem era suposto ser protegido pela campanha de controlo. ‚ÄòPower/knowledge‚Äô tal como n√£o foi descrito por Foucault. [3] √â sabido mas valer√° a pena relembrar que a ind√∫stria mineira de Katanga faz parte da hist√≥ria mais alargada, passada e presente, da avidez colonial e neo-colonial, e da hist√≥ria da luta congolesa pela independ√™ncia e constru√ß√£o nacional. A exposi√ß√£o inclui uma obra que retrata o local, em Katanga, onde Patrice Lumumba (1925-1961), o l√≠der da independ√™ncia e o primeiro a ser eleito democraticamente como Primeiro Ministro da RDC, foi assassinado, juntamente com Maurice Mpolo e Joseph Okito, por ordem de Joseph Mobutu, do secessionista Mo√Øse Tshombe, e com o apoio do governo belga e do ocidente, interessados nos recursos minerais da regi√£o e na secess√£o de Katanga (Fig. 5). Os assassinos destru√≠ram completamente o corpo de Lumumba na tentativa de apagar qualquer ind√≠cio do crime, mas, apesar disso, os habitantes de Katanga constru√≠ram um monumento em sua mem√≥ria ‚Äì um monumento que, n√£o contendo nenhuns restos mortais, foi fotografado por Baloji num contra-gesto, semelhante ao dos outros locais, de mem√≥ria e de concess√£o de visibilidade e presen√ßa ao que se tornara criminosamente ausente. [4] Como vimos, a exposi√ß√£o examina a quest√£o complexa, passada e presente, de um suposto desenvolvimento. O questionamento, no presente hist√≥rico, daquilo que desenvolvimento poder√° significar surge n√£o s√≥ nas paisagens p√≥s-industriais marcadas pela ind√∫stria de extrac√ß√£o, n√£o s√≥ nos planos urban√≠sticos supostamente modernizadores e higienizantes quando na realidade segregacionistas, ou nas ru√≠nas arquitect√≥nicas modernistas. Pois ‚Äòdesenvolvimento‚Äô √© igualmente investigado em arquitecturas menos arruinadas (Fig. 6), isto √©, em novos desenvolvimentos urban√≠sticos e de habita√ß√£o, os guetos privados da classe m√©dia-alta que inscrevem outras formas de segrega√ß√£o na paisagem urbana, desta vez de Kinshasa, e que contrastam com a energia ca√≥tica do mercado na avenida Lumumba. No contexto das for√ßas externas de globaliza√ß√£o que operam no pa√≠s, orientais para al√©m de ocidentais, o desenvolvimento √© erigido sob a forma de constru√ß√µes fantasiosas e de bairros cuidados e protegidos, e estimulado atrav√©s da produ√ß√£o alienante de desejo consumista: como se pode ver na obra So Modern! Home interiors and Chinese posters, Lubumbashi, 2013, que √© a primeira a ser encontrada e a √∫ltima a ser deixada pelo visitante ao entrar e sair do Project Space 1, respectivamente. Mas a exposi√ß√£o √© uma medita√ß√£o cont√≠nua sobre o presente atrav√©s da hist√≥ria, na tentativa de desenterrar hist√≥rias e mem√≥rias traumaticamente reprimidas e estrategicamente apagadas, que fundamentalmente constituem o presente e que, por isso, devem ser examinadas para que o futuro possa ser feito e vivido de forma diferente. Assim, v√°rias camadas de passado e presente s√£o literalmente sobrepostas e justapostas nas fotomontagens de Album que √© exibido num espa√ßo erigido no centro do Project Space 1. O t√≠tulo desta s√©rie refere-se a um √°lbum fotogr√°fico, descrito no seu interior como Album de Photos, 1912-1913, Central Afrique, Zaire, atribu√≠do ao Cdt. Henry Pauwels e realizado nas regi√µes orientais do ent√£o chamado Congo belga entre 1911 e 1913. Foi mostrado a Baloji por France Lejeune, um coleccionador estabelecido em Meuchen, na B√©lgica, e retrata uma expedi√ß√£o de ca√ßa e investiga√ß√£o cujo prop√≥sito era coleccionar esp√©cimes animais para o Royal Museum for Central Africa em Tervuren, na B√©lgica. O √°lbum fascinou Baloji pela sua justaposi√ß√£o de cenas de ca√ßa e de carcassas de animais com retratos etnogr√°ficos de ‚Äòtipos‚Äô raciais, como a legenda contextualizadora do Album de Baloji explica. Mas o seu Album incorpora fragmentos de um outro √°lbum: o que foi realizado pelo jornalista e fot√≥grafo Chrispin Mvano, que Baloji conheceu quando viajou para Goma, enviado a trabalho para os campos de refugiados da guerra de Bulengo. Eles trocaram os seus √°lbuns: Baloji mostrou a Mvano o √°lbum que fizera a partir das images de Pauwels e Mvano mostrou a Baloji o seu pr√≥prio √°lbum de imagens de guerra, realizado ao longo de v√°rios anos na regi√£o onde nasceu. A partir destes encontros, nasceu o Album de Baloji em exibi√ß√£o: ele viajou at√© aos locais visitados por Pauwels com o prop√≥sito de documentar a guerra atrav√©s das suas pr√≥prias imagens e das de Mvano. Consequentemente, as fotomontagens s√£o um palimpsesto das fotografias de guerra, recentes e a cores, de Baloji e Mvano, e do antigo e pseudo-cient√≠fico √°lbum etnogr√°fico realizado por Pauwels e reproduzido por Baloji com a cortesia de Lejeune (Figs. 7-11). No seu Album, o papel da fotografia nas epistemologias coloniais da classifica√ß√£o antropol√≥gica de tipos, tanto animais como humanos, ou humanos tornados animais, assim como na constru√ß√£o do arquivo colonial de olhares fetichistas e sexualizados, apreendendo corpos negros em poses enquadradas, sob o pretexto da ci√™ncia e do conhecimento, √© tornado evidente e relacionado com hist√≥rias mais recentes de viol√™ncia e guerra. As guerras recentes que devastaram a RDC s√£o igualmente examinadas como evid√™ncia da desilus√£o p√≥s-colonial e do falhan√ßo do estado, ao mesmo tempo que se mostram as conex√µes geo-pol√≠ticas mais alargadas, passadas e presentes, dessa desilus√£o e desse falhan√ßo. Na parede ulterior e exterior do espa√ßo ocupado pelo Album, que se encontra diante da parede de vidro de Rivington Place atrav√©s da qual os transeuntes podem ver o que est√° exposto no interior e os visitantes tem acesso visual √Ý rua l√° fora, h√° um tr√≠ptico ‚Äì uma obra que poder√° escapar √Ý aten√ß√£o do visitante dentro da galeria devido √Ý sua localiza√ß√£o menos vis√≠vel, mas que dificilmente passar√° despercebida a quem passa na rua (Fig. 12). Entitulada Return to Authenticy! View of President Mobutu‚Äôs pagoda, N‚Äôsele, Kinshasa, 2013, esta √©, na verdade, a primeira obra da exposi√ß√£o (e legendada como tal; So Modern! Home interiors and Chinese posters, Lubumbashi, 2013, √© uma obra, na realidade, numerada como segunda), vis√≠vel ainda antes de se entrar em Rivington Place e depois de se deixar o edif√≠cio. Este tr√≠ptico constitui um outro momento da exposi√ß√£o no qual Baloji n√£o evita a confronta√ß√£o com os protagonistas p√≥s-coloniais desses falhan√ßos, assim como com a sua rela√ß√£o com for√ßas externas. Como √© sabido, Mobutu foi o pai da Zairianiza√ß√£o do pa√≠s nos anos setenta, um momento de suposto retorno √Ý autenticidade, enquando, na verdade, √≠a recebendo apoio permanente do Ocidente. Por conseguinte, a decis√£o de Baloji e dos curadores de colocar este tr√≠ptico em face da rua tamb√©m nos confronta a todos n√≥s que vivemos num dos cora√ß√µes do ‚Äòimp√©rio‚Äô. Esta refer√™ncia ao imp√©rio, presente e passado, conduz-nos aos andares superiores, at√© ao Project Space 2, onde se encontra o arquivo fotogr√°fico de Alice Seeley Harris (Fig. 13). Este arquivo foi raramente exposto (a √∫ltima vez que foi mostrado foi h√° 110 anos) e, nas palavras dos curadores, constitui ‚Äòaquilo que foi provavelmente a primeira campanha fotogr√°fica em defesa de direitos humanos‚Äô, uma vez que despoletou um debate p√∫blico internacional acerca das atrocidades cometidas pelo regime do Rei Leopoldo II no chamado Estado Livre do Congo. [5] Quando Harris e o seu marido, Reverend John Harris, come√ßaram a mostar as imagens desses abusos de direitos humanos na Europa e nos Estados Unidos sob a forma das chamadas ‚Äòlantern slide lectures‚Äô, o debate culminou em press√£o pol√≠tica internacional e no fim da propriedade privada do Congo por parte de Leopoldo, mantendo-se, contudo, a sua administra√ß√£o colonial por parte da B√©lgica. Congo Dialogues foi organizada em parceria com a Anti-Slavery International, da qual Harris foi membro activo e que det√©m o seu arquivo, e com o International Slavery Museum em Liverpool (que apresenta a exposi√ß√£o associada Brutal Exposure: The Congo para coincidir com Congo Dialogues) e pretende assinalar os 175 anos da Anti-Slavery International e da inven√ß√£o da fotografia. A sec√ß√£o dedicada ao arquivo de Harris inclui sessenta e duas imagens, organizadas de forma relativamente sequencial. A sequ√™ncia come√ßa com fotografias que retratam a presen√ßa de mission√°rios no Congo, incluindo o casal Harris, para se focar de seguida na explora√ß√£o de borracha, a fonte mais importante do enorme lucro de Leopoldo, e depois em imagens mais antropol√≥gicas e etnogr√°ficas de ‚Äòtipos‚Äô e, finalmente, nas imagens de tortura que se tornaram o foco das apresenta√ß√µes de ‚Äòlantern slides‚Äô (Figs. 14-15). A parede principal e central do espa√ßo √© a √∫nica iluminada com uma projec√ß√£o de slide de grandes dimens√µes de uma das imagens apresentadas nas paredes laterais: aquela em surge a pr√≥pria Harris, vestida de branco e rodeada por um grupo de jovens corpos negros e n√∫s, numa esp√©cie de forma√ß√£o em pir√¢mide onde ela ocupa lugar cimeiro e central (Fig. 16). Esta imagem foi apropriada e as suas hierarquias de representa√ß√£o expostas e contrariadas pela artista Ayana V. Jackson, uma fot√≥grafa que recentemente n√£o tem vindo a captar nenhum outro corpo sen√£o o seu pr√≥prio e o de colaboradores pr√≥ximos, e que tem procurado estrat√©gias visuais alternativas e cr√≠ticas em rela√ß√£o √Ý ‚Äòpoverty pornography‚Äô e a estere√≥tipos de ‚Äòafricanidade‚Äô, atrav√©s de um corpo de trabalho que constitui um outro exemplo de investiga√ß√£o cr√≠tica do arquivo visual colonial e das complexidades da fixa√ß√£o fotogr√°fica de sujeitos e de corpos (Figs. 17-20). O intuito do casal Harris foi tamb√©m o de exp√¥r, no seu caso, a hipocrisia de Leopoldo de explora√ß√£o brutal sob a capa da miss√£o civilizadora, dessa forma levantando a quest√£o crucial de nega√ß√£o que reside no √¢mago do projecto colonial Europeu: quem foi realmente b√°rbaro? Mas, ao mesmo tempo, √© imposs√≠vel escrever sobre esta exposi√ß√£o sem lembrar a condi√ß√£o do pr√≥prio casal Harris, evidente na projec√ß√£o de slide, de mission√°rios brancos privilegiados ‚Äì por conseguinte, parte integrante dessa suposta miss√£o civilizadora e do imp√©rio, no seu caso, o brit√¢nico [6] ‚Äì que viajaram para o Congo, e que puderam fotografar com a sua kodak, e assim denunciar viol√™ncia atrav√©s das suas ‚Äòlantern slide lectures‚Äô, den√∫ncia essa que continha os seus pr√≥prios problemas de viol√™ncia como representa√ß√£o. Esta quest√£o foi abordada no contexto de uma visita esclarecedora com o curador da exposi√ß√£o, Mark Sealy, que prontamente reconheceu que tais cumplicidades devem ser tidas em conta e a forma como elas emergem muito explicitamente n√£o s√≥ em algumas das imagens mais etnogr√°ficas, mas tamb√©m no tipo de linguagem imperial e colonialista que o visitante detecta enquanto ouve a ‚Äòlantern slide lecture‚Äô original The Congo Atrocities (1908), narrada por Lola Young OBE, Baroness Young of Hornsey (gravada em Londres em Dezembro de 2013), que constitui a banda sonora desta sec√ß√£o de Congo Dialogues. [7] O facto destas ambival√™ncias surgirem em imagens e em discurso oral poderia ter sido examinado mais explicitamente na pr√≥pria exposi√ß√£o, ainda que o seja, sem d√∫vida, na documenta√ß√£o que a acompanha, nomeadamente no ensaio de Sharon Sliwinski publicado no jornal da exposi√ß√£o. [8] Apesar das inescap√°veis cumplicidades ambivalentes que envolvem a figura do mission√°rio branco, bem intencionado e paternalista (figura essa que tem as suas variantes contempor√¢neas), e apesar do papel da fotografia n√£o s√≥ como ferramenta de den√∫ncia mas tamb√©m de classifica√ß√£o colonial e poder imperial, reconhece-se que a abertura e a exibi√ß√£o deste arquivo √© um gesto importante num momento em que a quest√£o das complexidades do arquivo colonial ganha proemin√™ncia e, acima de tudo, um espa√ßo mais alargado para uma cr√≠tica mais profunda nos estudos visuais e p√≥s-coloniais. [9] Esta exposi√ß√£o tamb√©m √© importante porque contraria o apagamento ao qual Alice Seeley Harris foi sujeita na pr√≥pria hist√≥ria desta campanha de direitos humanos. Ela foi a fot√≥grafa, mas os her√≥is da hist√≥ria t√™m sido o seu marido, John Harris, o c√¥nsul brit√¢nico Roger Casement, e o jornalista brit√¢nico Edmund Dean Morel [10] ‚Äì todos eles, incluindo Alice, membros da Congo Reform Association (CRA), entre outras figuras de relevo. [11] Mark Twain √© uma dessas outras figuras presentes na exposi√ß√£o, que, para al√©m das imagens e da narra√ß√£o audio, tamb√©m inclui exemplos da chamada ‚Äòreform literature‚Äô. Tendo a narrativa da obra de Twain de 1906, King Leopold‚Äôs Soliloquy, sido escrita a partir do ponto de vista de Leopoldo, h√° um momento em que a personagem principal devaneia contra a √∫nica testemunha que n√£o conseguiu subornar: a kodak. Esta passagem merece ser citada: ‚ÄúThe kodak has been a sole calamity to us. The most powerful enemy indeed. In the early years we had no trouble in getting the press to ‚Äòexpose‚Äô the tales of mutilations as slanders, lies, inventions of busy-body American missionaries and exasperated foreigners‚Ķ Yes, all things went harmoniously and pleasantly in those good days‚Ķ Then all of a sudden came the crash! That is to say, the incorruptible kodak ‚Äì and all harmony went to hell! The only witness I couldn‚Äôt bribe. Every Yankee missionary and every interrupted trader sent home and got one; and now ‚Äì oh, well, the pictures get sneaked around everywhere, in spite of all we can do to ferret them out and suppress them.‚Äù [12] Apesar das capacidades da fotografia no sentido de permitir mudan√ßas de consci√™ncia colectiva, apesar do papel indiscut√≠vel que desempenhou no contexto particular destes acontecimentos hist√≥ricos, em suma, apesar da enorme relev√¢ncia deste arquivo, √© imperativo n√£o ignorar o seu papel como ferramenta de imp√©rio e instrumento de poder, o desequil√≠brio entre aqueles que usaram a c√¢mara e aqueles cuja imagem foi enquadrada e captada, imagem muda sem nome, e a ilus√£o de que estimular emo√ß√£o atrav√©s da fantasmagoria do ‚Äòlantern show‚Äô de atrocidades poderia permitir interven√ß√£o em sofrimento remoto. √â, por isso, tamb√©m imperativo n√£o ignorar as ilus√µes de poder da fotografia, ‚Äòa cren√ßa de que ... a liberta√ß√£o do sofrimento de estranhos est√° nas m√£os de espectadores distantes‚Äô, e de fot√≥grafos distantes. [13] Este √©, de facto, um dos dilemas n√£o resolvidos da √©tica, pol√≠tica e est√©tica da fotografia, das suas for√ßas e fragilidades, dilema que possui complexidades muito espec√≠ficas em contextos coloniais hist√≥ricos e no nosso momento contempor√¢neo marcado por novas formas de imp√©rio, por tecnologia digital globalizada, e por uma reexamina√ß√£o do arquivo colonial, nomeadamente atrav√©s da pr√°tica art√≠stica. A quest√£o da dist√¢ncia e da proximidade constitui, por isso, uma dentre as muitas raz√µes pelas quais o di√°logo com a obra de Baloji se torna t√£o relevante nesta exposi√ß√£o. Congo Urban oferece um olhar pr√≥ximo em vez de distante sobre as contradi√ß√µes e as energias, os traumas e as esperan√ßas, passadas e presentes, locais, transnacionais e globais, da realidade congolesa: um olhar que se det√©m em corpos, mas principalmente nas arquitecturas vazias e nos espa√ßos ocupados que esses corpos habitam, espa√ßos que o pr√≥prio Baloji habita a maior parte das vezes, ainda que n√£o de forma permanente; [14] um olhar que apropria olhares coloniais e p√≥s-coloniais para que estes possam ser examinados criticamente nos seus efeitos passados e presentes; [15] finalmente, um olhar menos propenso a, mas n√£o desprovido de, desequil√≠brios de poder, que emergem inevitavelmente a partir do momento em que qualquer pessoa segura uma c√¢mara, se move para captar imagens daqueles que ou n√£o se podem mover ou s√£o for√ßados a mover-se, e f√°-las circular ‚Äì o que, em √∫ltima an√°lise, confirma a for√ßa e a responsabilidade da fotografia. [Este ensaio n√£o foi escrito de acordo com o acordo ortogr√°fico e foi traduzido da vers√£o original em ingl√™s por Ana Balona de Oliveira.] Ana Balona de Oliveira √© Investigadora de P√≥s-doutoramento no Centro de Estudos Comparatistas da Universidade de Lisboa e no Instituto de Hist√≥ria de Arte da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Professora Assistente no Courtauld Institute of Art, Universidade de Londres, e curadora independente. Notas [1] Sobre a distin√ß√£o entre ru√≠na como inerte, quer negligenciada, quer valorizada como memorial, e ru√≠na como processo cont√≠nuo de ‚Äòsocial ruination‚Äô que se manifesta nas forma√ß√µes imperiais que persistem nos detritos materias e nas paisagens arruinadas, ver Ann Laura Stoler (Ed.), Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2013). [2] Legenda da exposi√ß√£o. [3] Ver Robert J. C. Young, ‚ÄòFoucault on Race and Colonialism‚Äô, in New Formations 25 (1995), pp. 57-65. [4] Estes eventos foram encenados na pe√ßa A Season in the Congo, escrita por Aim√© C√©saire e traduzida por Ralph Manheim, que esteve em cena no Young Vic Theatre em Londres entre 6 de Julho e 24 de Agosto de 2013. Para uma leitura de outra obra art√≠stica importante sobre o assassinato de Lumumba e a no√ß√£o Derridiana de spectropoetics, ver TJ Demos, ‚ÄòSven Augustijnen‚Äôs Spectropoetics‚Äô, em Return to the Postcolony: Specters of Colonialism in Contemporary Art (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), pp. 19-44. [5] No original: ‚Äòwhat was probably the first photographic campaign in support of human rights‚Äô, folha de sala da exposi√ß√£o e cartaz-brochura da exposi√ß√£o. [6] Tamb√©m n√£o se podem esquecer as cumplicidades entre belgas e brit√¢nicos em termos do sucesso das pretens√µes de Leopoldo na Confer√™ncia de Berlim, uma vez que teve o apoio do explorador brit√¢nico Henry Morton Stanley. Foi igualmente a realidade do imp√©rio brit√¢nico que colocou o jornalista Edmund Dean Morel na posi√ß√£o de perceber o que estava a suceder no Congo por ter trabalhado numa empresa de transportes que fazia neg√≥cios com o Congo (ver Sharon Sliwinski, ‚ÄòThe Kodak on the Congo: The Childhood of Human Rights‚Äô, in Republic of the Congo, Autograph ABP Newspaper, non-numerated page. Uma vers√£o mais longa deste ensaio foi publicada originalmente em Journal of Visual Culture, Vol. 5, Issue 3 [December 2006]). [7] A visita √Ý exposi√ß√£o mencionada, com o curador e director da Autograph ABP Mark Sealy, teve lugar no dia 1 de Fevereiro. [8] Ver Sliwinski, ‚ÄòThe Kodak on the Congo: The Childhood of Human Rights‚Äô, non-numerated page. [9] Ver Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton, N.J., Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2009); Christopher Pinney, Photography and Anthropology (London: Reaktion Books, 2011); Tamar Garb (Ed.), Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive, African Photography from the Walther Collection (G√∂ttingen: Steidl/The Walther Collection, 2013). [10] Edmund Dean Morel foi o autor da obra de 1906 Red Rubber, a qual, de acordo com Mark Sealy, constitu√≠u a fonte de inspira√ß√£o para a decis√£o curatorial de cobrir as paredes do Project Space 2 de vermelho, numa alus√£o √Ý viol√™ncia √Ý qual os trabalhadores da ind√∫stria de extrac√ß√£o de borracha eram sujeitos (Mark Sealy, visita √Ý exposi√ß√£o, Rivington Place, 1 de Fevereiro de 2014). [11] See Sliwinski, ‚ÄòThe Kodak on the Congo‚Äô, non-numerated page. [12] Mark Twain‚Äôs King Leopold‚Äôs Soliloquy citado em Sliwinski, ‚ÄòThe Kodak on the Congo‚Äô, non-numerated page. O t√≠tulo da exposi√ß√£o, como ficou evidente, √© uma cita√ß√£o de Twain. O it√°lico n√£o se encontra no original. [13] In the original: ‚Äòthe belief that ‚Ķ the liberation of strangers‚Äô suffering is in the hands of distant spectators‚Äô (Sliwinski, ‚ÄòThe Kodak on the Congo‚Äô, non-numerated page). [14] Baloji divide o seu tempo entre Bruxelas e Lubumbashi, onde, juntamente com Patrick Mudekereza, co-fundou a associa√ß√£o sem fins lucrativos Picha ASBL durante a primeira edi√ß√£o dos Picha Rencontres/Lubumbashi Biennale em 2008. A associa√ß√£o foi fundada com o intuito de apoiar o desenvolvimento de pr√°ticas art√≠sticas localmente. Esta exposi√ß√£o ser√° exibida em Lubumbashi, para al√©m de Bruxelas. [15] O corpo de trabalho que tem sido exibido em The Beautiful Time: Photography by Sammy Baloji, uma exposi√ß√£o que teve lugar no Museum for African Art em Nova Iorque em 2010, e que foi acompanhada pelo cat√°logo com o mesmo t√≠tulo, √© composto de fotografias a cores de ru√≠nas p√≥s-industriais da ind√∫stria mineira em Katanga, na linha das que s√£o expostas em Congo Urban, mas com uma abordagem da fotomontagem com material de arquivo que as aproxima das estrat√©gias usadas em Album. A sobreposi√ß√£o digital de imagens fotogr√°ficas a preto e branco de corpos de trabalhadores das minas, administradores coloniais, e at√© de Mobutu em visita a uma √°rea industrial, recuperadas de arquivos coloniais, industriais e da imprensa controlada pelo estado, nas fotografias a cores de paisagens p√≥s-industriais do pr√≥prio Baloji permitiu-lhe tornar essas ru√≠nas abandonadas do presente n√£o s√≥ habitadas sem que se captassem corpos fotograficamente, mas tamb√©m, significativamente, habitadas pelos espectros do passado, que s√£o, na verdade, habitantes do presente e que requerem examina√ß√£o (Fig. 21) (ver The Beautiful Time: Photography by Sammy Baloji [exh. cat.], ed. Kyle Bentley [New York: Museum for African Art, 2010]). H√° uma obra videogr√°fica, contudo, ‚Äì M√©moire (2007) ‚Äì onde o olhar de Baloji se deteve num corpo em particular: o do seu colaborador, o performer congol√™s Faustin Linyekula, que foi retratado movendo-se em paisagens em ru√≠na, atrav√©s de constrangimento mas tamb√©m de energia (ver The Beautiful Time, pp. 14-15). Este v√≠deo vai ser exibido no contexto de Congo Dialogues. [16] Inscri√ß√£o no verso: ‚ÄòLubumbashi MOI, Fly control campaign: each worker must bring 50 flies in order to receive his daily ration. 30 October 1929‚Äô. [17] The site where Patrice Lumumba, Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito were executed and first buried. [18] May 2013, Kanyaruchinya, North of Goma. Indian UN peacekeepers establish a road block between the rebel groups and the Congolese national army. Civilians must show proof of identity before permission to cross is granted. [19] February 2012 Brussels. Demonstration by the Congolese diaspora against the last presidential elections and the war in the eastern region of the Congo. >>>>>> Original English version Sammy Baloji and Alice Seeley Harris in Dialogue: Against Leopold‚Äôs (and others‚Äô) Soliloquies Rivington Place, the London home of Autograph ABP and Iniva, has currently on view a remarkable exhibition of photography. Organised by Autograph ABP and curated by its director Mark Sealy and by the associate curator Ren√©e Mussai, this exhibition establishes a dialogue, made explicit in the exhibition title ‚ÄòWhen Harmony Went to Hell‚Äô, Congo Dialogues: Alice Seeley Harris and Sammy Baloji, between two very distinct bodies of photographic work: an ongoing project by the Congolese photographer Sammy Baloji (b. Lubumbashi, DRC, 1978) entitled Congo Urban: Rhythms of Syncopation and Suspension, the first major solo exhibition of Baloji in the UK, which occupies Rivington Place‚Äôs major exhibiting space on the ground floor, Project Space 1, and involves collaboration with Filip De Boeck and Chrispin Mvano; and, in Project Space 2, the photographic archive, made by the British missionary Alice Seeley Harris (1870-1970) in 1904, of the atrocities committed by King Leopold II (1835-1909) in the territory which the European colonial nations and the United States decided, in the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, that he should administer privately ‚Äì the ironically named Congo Free State (1884-1908), present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo, Baloji‚Äôs country. Through the large-scale photographic series and the smaller photomontages that make up Congo Urban: Rhythms of Syncopation and Suspension, Baloji investigates how the colonial past keeps haunting the present in architectural and post-industrial ruins of modernity: [1] decaying yet re-appropriated modernist buildings in Kinshasa, rusty satellite dishes uselessly looming in the outskirts of the city, the abandoned structures of the mining industry (Fig. 1), the urban racial segregation, implemented in colonial times under the pretext of modernizing sanitation, woven into the fabric of Lubumbashi, the capital of the southeastern province of Katanga where Baloji was born and which is one of the richest copper, cobalt, and uranium mining areas of Central Africa (Fig. 2). Indeed, one of the most powerful components of Baloji‚Äôs exhibition is Photographic Essay on Urban Planning from 1910 to the present day in the city of Lubumbashi (2013). This is a large-scale, grid-like photographic composition with aerial views of Lubumbashi depicting a mining area and a sanitary belt which was planned at the beginning of the twentieth century by the colonial administration in order to protect the white population from malaria; hence, the grid-like juxtaposition of these aerial views, urban grids of control and separation, and yet other grid-like compositions: pseudo-scientific taxonomies of malaria-carrying mosquitoes, themselves also typical of the colonial epistemologies of obsessive classification, which Baloji found in a museum. In order to provide further context, this work is accompanied by a citation from The Development of the Congo, a special issue on the occasion of the International Exhibition at Elisabethville, colonial-time name of Lubumbashi, from 1931, in which R. Wins, a provincial engineer in Katanga, wrote as follows: ‚ÄúThe neutral zone avoids close contact between whites and blacks. An almost empty area measuring a minimum of 500 meters separates their two areas of settlement, this distance corresponding to that which a malaria-carrying mosquito will normally cover. The neutral zone thus divides the lives of blacks from those of whites: it keeps the latter safe from the sources of malaria, and from the rowdy activities of blacks, so creating completely independent living conditions for each race ‚Ķ it is a true cordon sanitaire, placed at a right angle from the prevailing winds ‚Ķ our urban planning contents itself with creating developments that satisfy conditions of hygiene, salubrity and security, giving the white and black races the opportunity to live according to the hopes and needs of each, however modest these might be.‚Äù [2] Indeed, apartheid was not exclusive to South Africa. Baloji adds yet another component to this moment of his exhibition: a photograph dated 30th October 1929 of two young black men sitting next to a pile of insects, with a verso inscription which reads as follows: ‚ÄòLubumbashi MOI, Fly control campaign: each worker must bring 50 flies in order to receive his daily ration, 30 October 1929‚Äô (Figs. 3-4). One now knows how the collection of mosquitoes photographed by Baloji was gathered by colonial scientists, how malaria was prevented, and who was supposed to be protected by the control campaign. Power/knowledge as it was not described by Foucault. [3] As is well known but worth recalling, the mining history of Katanga is part of the broader history, past and present, of colonial and neo-colonial greed, and of the history of Congolese struggle for independence and nation-building. The exhibition includes a photograph of the place in Katanga where Patrice Lumumba (1925-1961), the independence leader and first democratically elected Prime Minister of the DRC, was executed, together with Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, by order of Joseph Mobutu, of the secessionist Mo√Øse Tshombe, and with the support of the Belgian government and the West, interested in the mineral resources of the region and in the secession of Katanga (Fig. 5). The executioners completely destroyed Lumumba‚Äôs body in an attempt to erase any evidence of their crime, but the inhabitants of Katanga built a monument in his memory nonetheless ‚Äì the one which, guarding no remains, was photographed by Baloji in a counter-gesture, similar to the one performed by the other locals, of remembrance and of giving visibility and presence to what had been made criminally absent. [4] As we have seen, the exhibition addresses the complex issue, past and present, of so-called development. The questioning, in the historical present, of what development might mean emerges not only in the post-industrial landscapes marked by the extraction industry, in the supposedly modernizing and sanitizing while in fact segregationist urban plans, or in architectural modernist ruins. For ‚Äòdevelopment‚Äô is also investigated in less ruined architectures (Fig. 6), that is, in new urban and housing developments, the private middle- and upper-class ghettos which inscribe other forms of segregation on the urban landscape, this time of Kinshasa, and which contrast with the chaotic energy of the market in Lumumba Boulevard. In the context of the external forces of globalization operating in the country, Eastern besides Western, development is built in the form of fantasy constructions and enclosed neat neighborhoods, and stimulated as the alienating production of consumerist desire: as shown in the work So Modern! Home interiors and Chinese posters, Lubumbashi, 2013, which is the first to be encountered and the last to be left behind by the viewer as he or she enters and leaves Project Space 1, respectively. But the exhibition is a continuous meditation on the present through history, in an attempt to unearth traumatically repressed and strategically erased histories and memories which fundamentally constitute the present and therefore need to be addressed if the future is to be made and lived differently. And so several layers of past and present are literally superimposed and juxtaposed in the photomontages of the Album which is displayed in a space centrally erected in Project Space 1. The title of this series refers to a photographic album, described in its inside cover as Album de Photos, 1912-1913, Central Afrique, Zaire, attributed to Cdt. Henry Pauwels and made in the eastern regions of the then Belgian Congo between 1911 and 1913. It was shown to Baloji by France Lejeune, a collector based in Meuchen, Belgium, and depicts a hunting research expedition whose purpose was to collect animal specimens for the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium. The album fascinated Baloji for its juxtaposition of hunting scenes and animal carcasses with ethnographic portraits of racial ‚Äòtypes‚Äô, as the contextualizing caption of Baloji‚Äôs own Album explains. But his Album incorporates fragments of yet another album: the one made by the journalist, photographer and fixer Chrispin Mvano, who Baloji met when he travelled to Goma on an assignment in the refugee camps of the war in Bulengo. They exchanged their albums: Baloji showed Mvano the album he had made from Pauwels‚Äôs images and Mvano showed Bajoli his own album of war photographs, made over several years in the region where he was born. From these encounters sprang Baloji‚Äôs Album on view: he travelled to the places visited by Pauwels with the purpose of documenting the war through his own and Mvavo‚Äôs images. So the photomontages are a palimpsest of recent colour war photographs by Baloji and Mvano, and of the old, pseudo-scientific and ethnographic album made by Pauwels and reproduced by Baloji with the courtesy of Lejeune (Figs. 7-11). There, photography‚Äôs role in the colonial epistemologies of the anthropological classification of types, both animal and human, or human made animal, as well as in the construction of the colonial archive of fetishistic, sexualized gazes arresting black bodies in framed poses, under the pretext of science and knowledge, is made evident and connected to more recent histories of violence and war. The recent wars that have ravaged the DRC are also addressed as evidence of post-colonial disillusionment and state failure, while the broader geopolitical connections, past and present, of such disillusionment and failure are shown. On the exterior back wall of the Album‚Äôs space, which faces Rivington Place‚Äôs glass wall through which passers-by can look at what is on view indoors and viewers can see the street outside, there is a triptych ‚Äì a work which might escape the viewer‚Äôs attention inside the gallery due to its hidden location but which can hardly be missed by whoever walks on the street (Fig. 12). Titled Return to Authenticy! View of President Mobutu‚Äôs pagoda, N‚Äôsele, Kinshasa, 2013, this is actually the first work of the exhibition (and captioned as such; So Modern! Home interiors and Chinese posters, Lubumbashi, 2013, is actually numbered as second), visible even before entering Rivington Place and after leaving the building. This triptych is yet another moment in the exhibition by means of which Baloji does not avoid the confrontation with the post-colonial protagonists of such failures, as well as with their relation to external forces. As is well known, Mobutu was the father of the Zairianization of the country in the 1970s, a moment of so-called return to authenticity, while being in fact supported by the West all along. So Baloji‚Äôs and the curators‚Äô decision to place this triptych facing the street also confronts all of us who live in one of the hearts of ‚Äòempire‚Äô. This reference to empire, present and past, leads us upstairs to Project Space 2, where one finds Alice Seeley Harris‚Äôs photographic archive (Fig. 13). This is a rarely seen archive (the last time it was shown was 110 years ago) which, in the words of the curators, constitutes ‚Äòwhat was probably the first photographic campaign in support of human rights‚Äô, as it did prompt an international public debate around the atrocities committed by the regime of King Leopold II in the Congo Free State. [5] When Harris and her husband, Reverend John Harris, started showing the images of such human rights abuses in Europe and the United States in the format of lantern slide lectures, the debate culminated in international political pressure and the end of Leopold‚Äôs private ownership of the Congo, if not of its colonial administration by Belgium. Congo Dialogues was organized in partnership with Anti-Slavery International, of which Harris was an active member and which holds her archive, and the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool (which presents the associated exhibition Brutal Exposure: The Congo to coincide with Congo Dialogues) and intends to mark the 175th anniversary of Anti-Slavery International and the invention of photography. The section devoted to Harris‚Äôs archive comprises sixty-two images more or less organized in a sequence. This begins with photographs depicting the presence of missionaries in the Congo, including the Harrises, then to focus on the exploitation of rubber, the most important source of Leopold‚Äôs enormous profit, moving on to more anthropological and ethnographic images of ‚Äòtypes‚Äô, and finally the images of torture which became the focus of the lantern slide shows (Figs. 14-15). The main central wall of the space is the only one illuminated with a large-scale slide projection of one of the images presented in the lateral walls: the one featuring Harris herself, dressed in white and surrounded by a group of young, nude, black bodies, in a sort of pyramidal formation where she occupies upper central stage (Fig. 16). This image has been appropriated and its hierarchies of representation exposed and countered by the artist Ayana V. Jackson, a photographer who recently has been capturing no other body but her own and that of close collaborators, and who has been looking for visual strategies alternative to and critical of ‚Äòpoverty pornography‚Äô and stereotypes of ‚ÄòAfricanness‚Äô, by means of a body of work which constitutes yet another example of a critical engagement with the colonial visual archive and with the complexities of the photographic arrest of subjects and bodies (Figs. 17-20). The intent of the Harrises was also to expose, in their case, Leopold‚Äôs hypocrisy of brute exploitation under the guise of the civilizing mission, thus raising the crucial question of denial which lies at the core of the European colonial enterprise: who was the real barbarian? But, at the same time, one cannot write about this exhibition without calling to mind the Harrises own status, evident in the slide projection, as privileged white missionaries ‚Äì thus also an integral part of that so-called civilizing mission and of empire, in their case, the British [6] ‚Äì travelling to the Congo, being able to photograph with their kodak, and to denounce violence through their lantern slide lectures, a denunciation which contained its own problems of violence as representation. This question was addressed in the context of an enlightening tour with the exhibition curator, Mark Sealy, who promptly acknowledged that such complicities must be taken into account and how they emerge very explicitly not only in some of the more ethnographic images, but also in the sort of imperial, colonialist language which the visitor hears when listening to the original lantern slide lecture The Congo Atrocities (1908), narrated by Lola Young OBE, Baroness Young of Hornsey (recorded in London in December 2013), which constitutes the soundtrack of this section of Congo Dialogues. [7] That these ambivalences do emerge in images and aural speech could have been addressed more explicitly in the exhibition, although they are indeed discussed in the accompanying documentation, notably in the essay by Sharon Sliwinski published in the exhibition newspaper. [8] Despite these inescapable ambivalent complexities surrounding the figure of the white, well-intentioned, and patronizing missionary (a figure which has its contemporary equivalents), as well as the role of photography as not only tool of denunciation but also of colonial classification and imperial power, the opening up and the exhibiting of this archive remains an important gesture at a moment when the question of the complexities of the colonial archive is gaining prominence and, more importantly, a wider space for increased criticality in visual and post-colonial studies. [9] This exhibition is also important because it counters the erasure to which Alice Seeley Harris has been subjected in the very history of this human rights campaign. She was the photographer but the usual heroes of the story have been her husband, John Harris, the British Consul Roger Casement, and the British journalist Edmund Dean Morel [10] ‚Äì all of them, including Alice, members of the Congo Reform Association (CRA), among other relevant figures. [11] Mark Twain is one of those other figures featured in the exhibition, which, besides the images and the audio narration, also includes examples of reform literature. The narrative of Twain‚Äôs 1906 King Leopold‚Äôs Soliloquy having been written from the point of view of Leopold, there is a moment when the main character muses against the sole witness he could not bribe: the kodak. This passage is worth quoting in full: ‚ÄúThe kodak has been a sole calamity to us. The most powerful enemy indeed. In the early years we had no trouble in getting the press to ‚Äòexpose‚Äô the tales of mutilations as slanders, lies, inventions of busy-body American missionaries and exasperated foreigners‚Ķ Yes, all things went harmoniously and pleasantly in those good days‚Ķ Then all of a sudden came the crash! That is to say, the incorruptible kodak ‚Äì and all harmony went to hell! The only witness I couldn‚Äôt bribe. Every Yankee missionary and every interrupted trader sent home and got one; and now ‚Äì oh, well, the pictures get sneaked around everywhere, in spite of all we can do to ferret them out and suppress them.‚Äù [12] Despite photography‚Äôs capacities for eliciting changes in public awareness, despite the indisputable role it performed in the particular context of these historical events, in short, despite the enormous relevance of this archive, it is imperative to not ignore its role as tool of empire and instrument of power, the imbalance between those who held the camera and those whose image was framed and captured, a mute image with no name, and the illusion that arousing affect through the phantasmagoria of the atrocity lantern show could bring about intervention in remote suffering. It is thus also imperative to not ignore photography‚Äôs illusions of power, ‚Äòthe belief that ‚Ķ the liberation of strangers‚Äô suffering is in the hands of distant spectators‚Äô, and distant photographers. [13] This is one of the unresolved dilemmas of photography‚Äôs ethics, politics, and aesthetics, its strengths and weaknesses, which has very specific complexities in historical colonial settings and in our own contemporary moment marked by new forms of empire, by globalized digital technology, and by a reengagement with the colonial archive, notably through artistic practice. The question of distance and proximity thus constitutes one of the many reasons why the dialogue with Baloji‚Äôs work becomes so relevant in this exhibition. For Congo Urban provides a close rather than distant gaze into the past and present, the local, transnational, and global contradictions and energies, traumas and hopes of Congolese reality: a gaze which looks at bodies but mostly at the empty architectures and the crowded urban spaces they inhabit, and which are spaces inhabited by Baloji himself most of the times, though not all the time; [14] a gaze which appropriates colonial and post-colonial gazes so that they can be critically scrutinized in their past and present effects; [15] finally, a gaze less prone to, if not totally exempt of, power imbalances, which inevitably emerge as soon as anyone holds a camera, moves in order to capture the images of those who either cannot or have been forced to move, and makes them circulate ‚Äì which, ultimately, is a testament to photography‚Äôs strength and responsibility. Ana Balona de Oliveira is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Centre for Comparative Studies of the University of Lisbon and at the Institute for Art History of the New University of Lisbon, a Visiting Lecturer at the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, and an independent curator. Notes [1] On the useful distinction between ruin as inert, either neglected or valorised memorial, and ruin as a continuous process of social ruination of peoples‚Äô lives manifest in the imperial formations which persist in material debris and ruined landscapes, see Ann Laura Stoler (Ed.), Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2013). [2] Exhibition caption. [3] See Robert J. C. Young, ‚ÄòFoucault on Race and Colonialism‚Äô, in New Formations 25 (1995), pp. 57-65. [4] These events were re-enacted in the play A Season in the Congo, written by Aim√© C√©saire and translated by Ralph Manheim, which was on view at the Young Vic Theatre in London between 6 July and 24 August. For a reading of another important artistic work on Lumumba‚Äôs assassination and the Derridian notion of spectropoetics, see TJ Demos, ‚ÄòSven Augustijnen‚Äôs Spectropoetics‚Äô, in Return to the Postcolony: Specters of Colonialism in Contemporary Art (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), pp. 19-44. [5] Exhibition press release and exhibition poster and leaflet. [6] The complicities between Belgians and British cannot be forgotten also in terms of the success of Leopold‚Äôs endeavours in the Berlin Conference, since he had the support of the British explorer Henry Morton Stanley. It was also the reality of the British Empire that allowed the journalist Edmund Dean Morel to realise what was happening in the Congo when he was an employee of a shipping company doing business in the Congo (see Sharon Sliwinski, ‚ÄòThe Kodak on the Congo: The Childhood of Human Rights‚Äô, in Republic of the Congo, Autograph ABP Newspaper, non-numerated page. A longer version of this essay originally appeared in the Journal of Visual Culture, Vol. 5, Issue 3 [December 2006]). [7] The aforementioned exhibition tour with curator and Autograph ABP director Mark Sealy took place on 1 February. [8] See Sliwinski, ‚ÄòThe Kodak on the Congo: The Childhood of Human Rights‚Äô, non-numerated page. [9] See Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton, N.J., Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2009); Christopher Pinney, Photography and Anthropology (London: Reaktion Books, 2011); Tamar Garb (Ed.), Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive, African Photography from the Walther Collection (G√∂ttingen: Steidl/The Walther Collection, 2013). [10] Edmund Dean Morel was the author of the 1906 book Red Rubber, which, according to Mark Sealy, was the source of inspiration for the curatorial decision of having Project Space 2‚Äôs walls covered in red in an allusion to the violence to which the labourers of the rubber extraction industry were subjected (Mark Sealy, exhibition tour, Rivington Place, 1 February 2014). [11] See Sliwinski, ‚ÄòThe Kodak on the Congo‚Äô, non-numerated page. [12] Mark Twain‚Äôs King Leopold‚Äôs Soliloquy quoted in Sliwinski, ‚ÄòThe Kodak on the Congo‚Äô, non-numerated page. The title of the exhibition, as has just become evident, is quoted from Twain. My italics. [13] Sliwinski, ‚ÄòThe Kodak on the Congo‚Äô, non-numerated page. [14] Baloji divides his time between Brussels and Lubumbashi, where he and Patrick Mudekereza have co-founded the not-for-profit association Picha ASBL during the hosting of the first edition of the Picha Encounters/Lubumbashi Biennale in 2008. The association was founded with the purpose of supporting the development of artistic practice locally. This exhibition is going to be shown in Lubumbashi, besides Brussels. [15] The body of work which has been exhibited in The Beautiful Time: Photography by Sammy Baloji, an exhibition which took place at the Museum for African Art, New York, in 2010, and which was accompanied by a catalogue with the same title, is comprised of colour photographs of post-industrial ruins of the mining industry in Katanga in the vein of those exhibited in Congo Urban, but with an approach to photomontage with archival material which makes it close to the strategies used in the Album. The digital superimposition of photographic images in black and white of the bodies of mine labourers, colonial administrators, and even of Mobutu on visit to an industrial site, retrieved from colonial, industrial, and state-controlled media archives, on Baloji‚Äôs own colour photographs of post-industrial landscapes has allowed him to make those abandoned ruins of the present not only inhabited without his actually photographically arresting bodies, but also, most significantly, inhabited by spectres of the past which are, in actual fact, inhabitants of the present and in need of address (Fig. 21) (see The Beautiful Time: Photography by Sammy Baloji [exh. cat.], ed. Kyle Bentley [New York: Museum for African Art, 2010]). There is one video work, however, ‚Äì M√©moire (2007) ‚Äì where Baloji‚Äôs gaze was directed at a particular body: that of his collaborator, the Congolese performance artist Faustin Linyekula, who was portrayed moving in ruined landscapes through constraint but also energy (see The Beautiful Time, pp. 14-15). This video will be exhibited in the context of Congo Dialogues. [16] Inscription verso reads: ‚ÄòLubumbashi MOI, Fly control campaign: each worker must bring 50 flies in order to receive his daily ration. 30 October 1929‚Äô. [17] The site where Patrice Lumumba, Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito were executed and first buried. [18] May 2013, Kanyaruchinya, North of Goma. Indian UN peacekeepers establish a road block between the rebel groups and the Congolese national army. Civilians must show proof of identity before permission to cross is granted. [19] February 2012 Brussels. Demonstration by the Congolese diaspora against the last presidential elections and the war in the eastern region of the Congo.

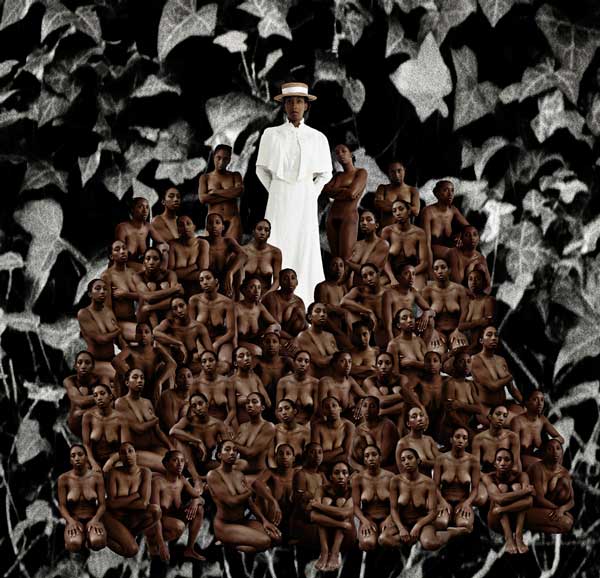

|